We had a discussion of the idea of Mental Models that was presented in the previous lecture. We first took a round where each of the groups gave a presentation of their results from the practical exercise. The exercise was to find evidence for mental models in the way that people use interactive products.

Six groups gave presentations on the following topics:

- Mobile Phone: How to find the calendar function on an unfamiliar phone.

- Mobile Phone: Taking a picture with the phone camera and setting it as the background image. Sending an SMS message.

- Digital Camera: Exploring the functions of an unfamiliar digital camera.

- Mobile Phone: Sending a message as well as the general understanding of the phone.

- Dishwasher: Differences in the ways that men and women think of what happens after you press start.

- Microwave: How different people think the microwave works.

We then looked back over some of the questions raised in last week’s lecture and discussed them in relation to the results of the practical task.

Kinds of mental model

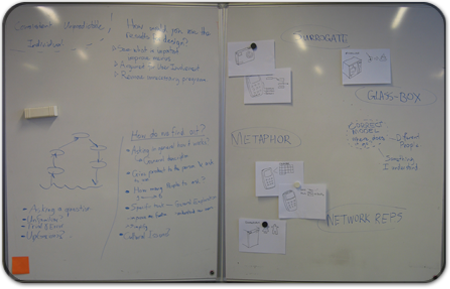

The four kinds of mental model identified by Carroll & Olson (1988) and presented in the lecture were:

- Surrogate: A model that mimics the output of a system, but not the internal workings.

- Metaphor models: You understand a product by comparing it to something else that you already know.

- Glass Box models: Somewhere between a surrogate and metaphor model. A composite of different metaphors that together can describe the system.

- Network representations: Understanding a product as a series of states with transitions between them.

Students from each group tried to say which of these models characterized the kind of models they had seen. The white-board on the right side of the picture above shows what we ended up with. All groups found that their examples contained bits and pieces of different categories. It didn’t seem that there was one way that people thought about the products, but rather a combination of different ways.

There was also a discussion of where a correct model would be put, if we had one. We wondered how one would determine if a model was correct or not and supposed that this determination would depend on criteria of the person holding the model. Therefore it’s probably not possible to single out one model as the correct one.

Staged model of human action

We discussed whether the people the students had interviewed had seemed to act like the staged model of human action presented in the lecture. Students suggested that when people are asked a question that they have to think about, or when they are presented with an unfamiliar situation that it might be like this. There was also an example from the practical task where the person interviewed had gone into trial and error in his attempt to get the mobile phone to work. Perhaps a trial and error kind of activity would fit with this model. We also discussed that not all the levels in the model are processes that we are conscious of.

How do we find out about mental models?

Groups had gone about interviewing people to find out about their mental models in a variety of ways:

- Asking in general how a product works (Microwave, Dishwasher).

- Give a product to the person and ask them to use it (Phones, Camera).

- Set a specific task for the person to do (Phones).

- Ask the person to explore the interface and explain what they are doing (Camera).

- Interview just one person, or several.

Was any of the information gained useful for design?

Does the mental model theory help us as designers? We asked whether there information had emerged from the practical task that could be useful for improving the products studied. Students made the following suggestions:

- You can see what is important to people. This could be used to improve the organization of the camera menus for instance.

- It could provide an argument for further user involvement in the design process. If you could take ‘mental models’ of prospective users back to an organization, it might help convince them that users sometimes see their products in different ways.

- You could remove unnecessary programs. In the dishwasher, it seemed that few people used the settings of the dishwasher beyond choosing an automatic program.

- Understanding the mental model could be used to make a product more consistent, or alternatively to make it more unpredictable (e.g. in a game). In the second case, a designer might still find it useful to be aware of the likely mental model of users so that they can make the product to unpredictable things. There is also a tension between the desire for a consistent model, and the differences between how different people conceive of products.

Did we find a mental model?

My own feeling is that there didn’t seem to be a clear case of a mental model in any of the presentations beyond what one might characterize as just knowledge about how things work.

We didn’t see much evidence in the presentations of how people’s product use related to their social or professional circumstances or to the physical environment. As we will see in future classes, these are all areas that other theories in HCI have paid more attention to and shown to be important. Maybe the focus on mental models in this practical task lead us to overlook these.

An intriguing result of the practical exercise was that students in several groups not only found out about how people conceive of a product (their mental model) but also some strategies they use when trying to figure it out. Examples were, ‘getting an overview’, ‘trial and error’ and ‘relying on the preset routine’. These ‘use strategies’ seemed an important part of how people used the products, but aren’t addressed by the theory that people have mental models.

However, the notion of mental models did seem useful to the students in how they organized and went about the task. It seemed to give them a worthwhile objective to inquire after. It also seemed to provide a common language for ho we discussed people’s use of the products.